Have you ever found yourself reaching for a tub of ice cream after a stressful day at work? Or perhaps diving into a bag of chips when you’re feeling bored or lonely? If so, you’re not alone. Many of us have

experienced the phenomenon known as emotional eating, where our emotions

influence our food choices and eating behaviours.

To understand emotional eating, it’s essential to delve into the complex relationship between emotions and food throughout human history.

Our ancestors’ survival instincts and environmental challenges played a

significant role in shaping their eating habits. Early humans learned to seek

out calorie-dense foods to ensure their survival in times of scarcity, a behaviour that still manifests today in our preference for high-fat and high-sugar comfort foods.

Understanding Emotional Eating

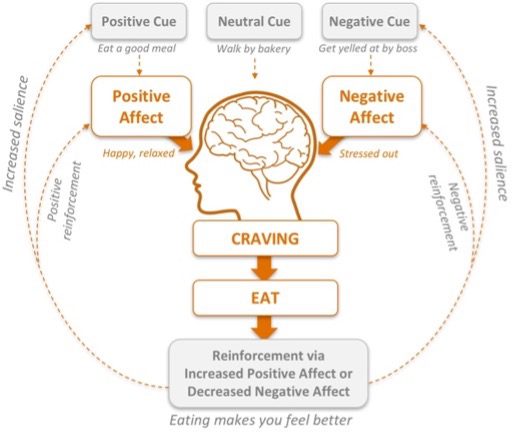

Emotional eating is a coping mechanism that many people turn to in response to various emotional triggers, such as stress, boredom, sadness, or even happiness. When faced with intense emotions, the brain’s reward system can become activated, driving us to seek out pleasurable experiences, often in the form of food. Comfort foods, rich in sugar and fat, are particularly appealing during these times, as they trigger the release of feel-good

neurotransmitters like dopamine, temporarily alleviating negative emotions.

Our eating habits are heavily influenced by the way our brains learn to associate food with pleasure or relief from negative emotions. When we eat something enjoyable, our brains create strong memories that make us want to

eat that food again in similar situations. Similarly, if we eat to cope with

sadness or stress, our brains remember that too. Over time, these habits can

become ingrained, leading to cycles of overeating or restrictive eating

(Epstein et al., 2007; Dayan and Niv, 2008; Singh et al., 2010).

Additionally, highly processed foods, especially those high in sugar, fat, and salt, can affect our brains in ways similar to addictive substances. These foods trigger the release of dopamine, a feel-good chemical, making us crave them more and more. This can lead to habits where we eat not because we’re hungry, but because we’ve learned to associate certain foods with pleasure or relief from negative feelings (Rada et al., 2005; Avena et al.,

2006, 2008; Epstein et al., 2007; Lenoir et al., 2007; Stice et al., 2013).

Understanding these patterns can help us develop strategies to break unhealthy eating habits and build a healthier relationship with food.

Strategies for Managing Emotional Eating:

While emotional eating is a common phenomenon, there are strategies that individuals can employ to manage it effectively.

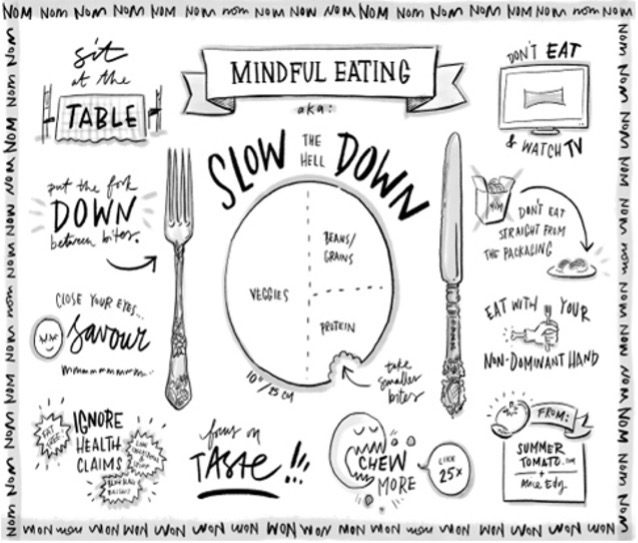

Practicing mindfulness and self-awareness can help individuals recognize the emotional triggers that prompt them to eat. Engaging in stress-reducing activities such as meditation, exercise, or spending time with loved ones can provide alternative coping mechanisms for dealing with emotions. Additionally, creating a supportive environment by stocking the kitchen with healthy, nourishing foods can help reduce the temptation to indulge in comfort eating.

In conclusion, emotions play a significant role in shaping our eating habits and food choices. By understanding the link between emotions and eating behaviours, we can take proactive steps to manage emotional eating and develop a healthier relationship with food. Remember, it’s okay to indulge in comfort foods occasionally, but it’s essential to find balance and practice moderation. By prioritizing self-care and adopting mindful eating practices, we can nourish our bodies and minds in a way that supports overall well-being.

References:

Epstein, L. H., Leddy, J. J., Temple, J. L., & Faith, M. S. (2007). Food reinforcement and eating: a multilevel analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 133(5), 884–906.

Dayan, P., & Niv, Y. (2008). Reinforcement learning: the good, the bad and the ugly. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 18(2), 185–196.

Singh, M., Kassi, A., & Kyaw, A. M. (2010). Operant Conditioning. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

Rada, P., Avena, N. M., & Hoebel, B. G. (2005). Daily bingeing on sugar repeatedly releases dopamine in the accumbens shell. Neuroscience, 134(3), 737–744.

Avena, N. M., Rada, P., & Hoebel, B. G. (2006). Evidence for sugar addiction: behavioral and neurochemical effects of intermittent, excessive sugar intake. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 32(1), 20–39.

Lenoir, M., Serre, F., Cantin, L., & Ahmed, S. H. (2007). Intense sweetness surpasses cocaine reward. PLOS ONE, 2(8), e698.

Stice, E., Yokum, S., Blum, K., & Bohon, C. (2013) Weight gain is associated with reduced striatal response to palatable food. The Journal of Neuroscience, 33(20), 8519–8527.

Join Weight Goals with Aba’s WhatsApp community and gain exclusive access to our hub of articles and recipes. Be part of a supportive community, receive valuable insights, and stay up-to-date with the latest in nutrition, fitness, lifestyle, and medicine. Elevate your weight goals journey by joining us today.

Talk to Aba